I had barely finished my January blog post when – THUD! – something rather heavy fell through the mail slot. I had been buying a lot of stuff online because of the Covid pandemic, so I had somewhat lost track of my orders: I knew it could be anything from frozen pizza to a framed picture of a disappointed horse. After unpacking, it turned out to be a book!

I’m not a great fan of crowdfunding but I have supported a few campaigns, mainly those aimed at documenting the history of the home computer era. As it coincided with my formative years, I now feel very strongly about things that help preserve the legacy of this wonderful technological age. So when it became known that an independent French publisher, Éditions 64K, had started an Indiegogo campaign for an extensive book about the Amiga demoscene, I was sold immediately. Considering how large and busy the scene had once been, it didn’t come as a surprise that the book got successfully funded in only two weeks.

Yet I wasn’t really expecting it when the book was delivered, mainly because the planned publishing date sounded a wee bit optimistic to me. Let me see: the campaign started in June 2020, with shipping expected for December. The publisher promised a mighty 450-page hardback covering approximately 90 demos from 1984 to 1993, in full colour print on quality paper. It was supposed to contain not only visual material but also a great deal of text describing the demos as well as giving interesting background on their development. I had previously worked for the publishing industry, so I knew you could easily deliver such a book in six months if your source material was more or less ready. But there were certain signals that the hay was nowhere near the barn. First of all, well into the campaign the publisher decided to change the title: the book was originally meant to be called – and was even promoted as – Demomaker, which admittedly was a major misnomer. Why’s that? Back in the early 90s, the Demomaker was an infamous Amiga program that allowed noobs and lamers to build simple demos from a set of ready-made effects and routines. Because such a program embodies a perfect antithesis of what the demoscene stands for, giving the book the same name would have been highly ironic.

Having chosen a much more appropriate title, the publisher then went on to announce a string of new sceners joining in and contributing their productions and stories. Which is great of course, but any such addition naturally inflates the project and adds to the production time. Given the ultimate number of contributors, combined with the fact that the demoscene is international and not all sceners are native speakers, it was clear the publisher would have a hell of a time organizing, editing, translating and proofreading the text content on top of all the graphic and typesetting work. I had a strong hunch that unless some corners were cut, Santa’s reindeer sleigh would end up short of cargo in December. So yes, the January delivery came as a nice surprise to me.

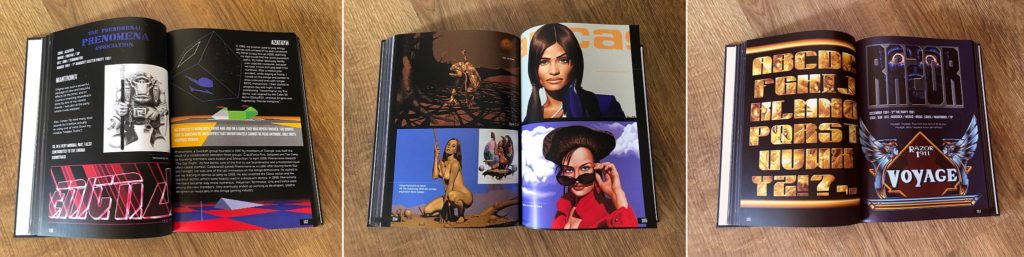

Upon unpacking I could immediately see that no expense was spared on the materials and binding. Chunky and substantial, the book presents itself as a formidable volume that will deserve a prominent position on your bookshelf. There is no dust jacket, but the cover is sturdy and very nice to the touch. It features pattern coating of glossy varnish and the book title is made in silver finish, which adds to the impression of a luxury item. Even just holding the book and flipping through its pages will make you feel that money has been well spent here.

As for the contents, I need to start with a small caveat. The book is called Demoscene, and the title may suggest that some kind of comprehensive account or analysis of the demo-making community is offered here. This is not the case, and let’s make it perfectly clear that such a thing was not the intended scope of the project. (If it were, the book would surely have to provide a more systematic coverage of two vital elements of scene life: diskmags and demoparties.) Instead, the book was conceived as a demo showcase right from the start, and indeed this is what you get in the first volume: ninety influential Amiga demos from the years 1984–1993. Although we need to add that the first three items were included mainly for historical reasons rather than for being actual demoscene productions.

If you followed the scene in the late 80s and early 90s, chances are high that you’ll be more than happy with the selection. I for sure can say that all of my personal favourites are there: the RSI Megademo by Red Sector – a demo I ran for weeks on end until the two disks developed serious read errors. Both megademos by Budbrain, showing that the scene didn’t lack a sense of humour and was not only about fame and competitiveness. The quirky Mental Hangover by Scoopex, a technological milestone that ushered us to the new dynamics of the trackmo era. Enigma by Phenomena with its phenomenal soundtrack. Digital Innovation by Anarchy, an unbelievable 30 minutes of graphics, effects and music squeezed on just one floppy disk. Hardwired by Crionics & The Silents and Desert Dream by Kefrens, epic demos that employed elements of film-inspired storytelling. And of course State of the Art by Spaceballs, a frantic visual performance that could easily be mistaken for a video taken from MTV. I could go on and on.

I’m glad the demos are presented in chronological order rather than alphabetically or sorted by group. An obvious advantage of this arrangement is that you can clearly see how the scene, its techniques, skills and aesthetics developed over the said period. You won’t fail to notice certain ugliness that is intrinsic to the early “megademo” phase, and the growing artistic aspirations of the post-1991 production. Better than any sociological study the book captures the predominantly adolescent male character of the scene, which reflects in demo themes (often inspired by the sceners’ reading lists of science fiction and fantasy) as well as in graphic artwork (obsession by the feminine, an element that the scene noticeably lacked). The visual material alone provides great insight and serves as a valuable document of the times.

But it was the text content I mainly bought the book for, and as far as new information is concerned, the volume certainly doesn’t disappoint. I have seen (and yawned over) retro-oriented publications that merely rehash well-known facts and then quote people with rose-tinted glasses on how great the Amiga was. This is not one of them: the book brings a look behind the scenes in the true sense of the phrase. Although the copyright page names Christophe Boucourt as author, the text is apparently not a systematic account written by one person; it was in fact co-authored and largely collected or adapted from various contributors directly associated with the demoscene. This makes the text content rather varied and somewhat lacking in coherence as a whole, but on the other hand it adds to authenticity because you know the information comes right from the horse’s mouth. The parts where sceners introduce their computing background may come across as a bit repetitive because the stories tend to be quite similar (“I had a Commodore 64 before I got an Amiga”), but otherwise the book is packed with interesting trivia and sheds a lot of light on scene life. Group wars and animosities, membership changes, rise to fame and fall to oblivion, the challenge of technology, creativity and the spirit of competition, long nights up getting things ready for the next day’s demo contest, parties raided by the police… it’s all there, testifying to the fact that the Amiga demoscene at the turn of the decades was a vibrant and a thoroughly unique subculture.

My only gripe about Demoscene: The Amiga Years, Volume 1 is the language quality of the book. As I hinted above in one of the opening paragraphs, corners had to be cut somewhere if such an ambitious project was to meet the no less ambitious deadline. I’m sorry to say that much as I appreciate the text content of Demoscene, the proofreaders really did a sloppy job here. I understand that the text incorporated pieces sent by a multitude of different people (sometimes in different languages) and that it wasn’t easy to unify the whole thing, so I’m fine with the style being sometimes a bit rough around the edges. Similarly I don’t get offended by the occasional factual mistake: the musician Moby could hardly have bought an Oric-1 computer in 1993 (p. 421); Cryptoburners’ demo wasn’t exactly called Hunt of 7th October (p. 92); there was no member of Kefrens called “Mellican” (p. 362), etc. However, what I cannot pass over in silence is the grammar and spelling errors, the number of which is beyond acceptable. I have no idea how much the proofreaders were paid for their work, and I’m sure the book was a labour of love and won’t make the publisher rich. But a project of such magnitude and of such immense documentary value certainly deserved better. I would have easily lived with a delay if only it had resulted in a more polished text, making the reading experience even more enjoyable.

Here’s hoping that the planned second volume will receive more love in the language department, and that this much-needed project will continue to cover other periods and areas of the demoscene. I’ll be eagerly waiting in line to chip in!

Boucourt, Christophe (ed.) Demoscene: The Amiga Years. Volume 1 (1984–1993). English edition. Biarritz: Éditions 64K, 2020. 447 pages. ISBN: 978-2-9575080-0-6.