Cieszyn is a quiet border town in Silesia, a historical region that now spans parts of Poland, Germany and the Czech Republic. It is in fact two towns, for fate and politics had it that after World War I and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Cieszyn got divided between Poland and the newly formed country of Czechoslovakia. It wasn’t a very fair split and it’s quite understandable why: with the majority of the local population being Polish, the larger part of the town including the nice historic centre went to Poland, while Czechoslovakia acquired the industrial suburbs in the west.

I remember that at the end of the 1980s, Czech Cieszyn was a run-down place where apathy and despair could be sold in quantity. Grey suburban ugliness shook hands with the communist town-planning butchery, and the ubiquitous feeling of decline was augmented by the grim border guards who, armed to the teeth, patrolled the two bridges separating the town from its Polish sibling. Far off the sightseeing map, the place gave you little reason to come for a visit. Yet I found myself travelling to Czech Cieszyn on an almost monthly basis, and so did many home-computing fans from my area. There was one particular reason why we would happily suffer two hours on a slow train and two hours back – and it certainly wasn’t the snack in the salmonella-infested railway station bistro. The reason was that the bookshops in Czech Cieszyn sold Polish books and magazines.

Now, that probably needs some explanation. At that time, Czechoslovakia was ruled by an authoritarian communist gerontocracy that neither welcomed nor understood modern technology. While in the West the home-computer revolution was in full swing, Czechoslovakia literally sneaked into the new era along the sidelines, thanks to enthusiastic individuals and local communities that found ways, often illegal, to fill in for the non-existent computer market. Surprisingly enough, obtaining hardware wasn’t the biggest problem (although the Iron Curtain was still firmly in place); in fact, by the end of the decade many Czech households owned a Sinclair, an Atari or a Commodore. But information was a precious commodity. The country’s only off-the-shelf magazine devoted to computer technology, Elektronika, largely focused on industrial applications in the Soviet Bloc, and provided little material on home computers. As a teenager with a shiny C64 on your desk, you really didn’t want to read about a bulky mainframe from Bulgaria.

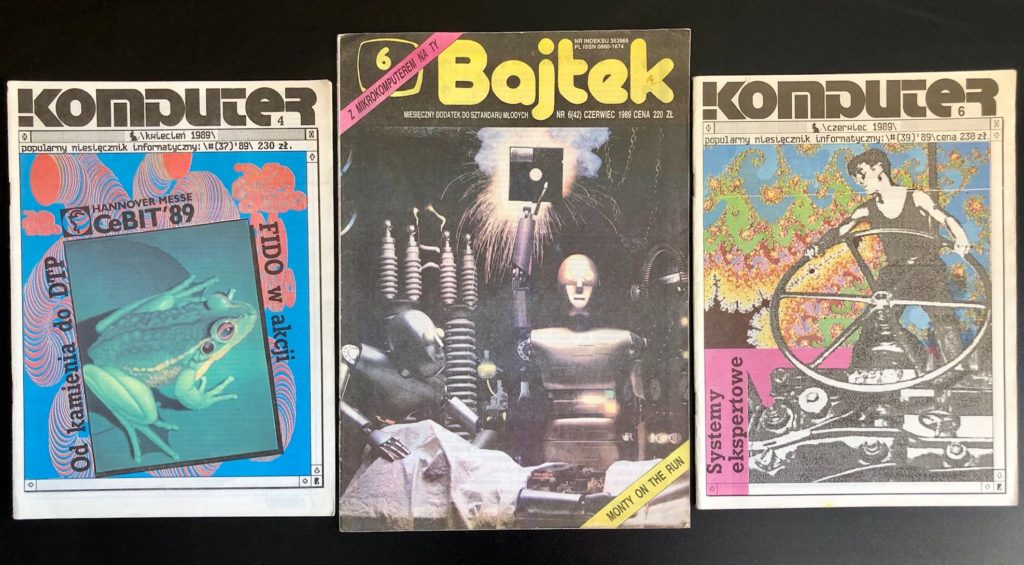

Things were very different in Poland, where computerization was taken more seriously. While also ruled by communists, the country actually had adopted a nationwide computer literacy programme, which went under the official slogan “The Game for Tomorrow.” The Polish government believed that encouraging young people to use computers productively would bring, at a later point, highly skilled workforce that would make an impact on the country’s ailing economy. Among the results of the official policy were two computer magazines that made us Czechs green with envy: Bajtek (which was mainly home-computer oriented) and Komputer (which focused on users from the professional sphere). Compared to our puny Elektronika, both magazines contained far less ideological fluff, and happily covered the latest technological developments in the West. And as a Slavic language, Polish represented a much lower barrier than the German we found in magazines occasionally smuggled from the neighbouring Austria or West Germany. So Bajtek and Komputer provided a good reason to hop on the train and take the lengthy Saturday trip to Czech Cieszyn. The refreshing read made the journey well worth it.

I know that history makes a point of repeating itself, but I’m still finding it hard to believe that – more than thirty years later – I’ve bought a Polish computer magazine again. Why did I bother, now that I can choose from about half a dozen different titles in my native language? Well, this particular mag has one great thing about it: it’s an active, Amiga-oriented print magazine that focuses on the next-generation branch of the platform. Which came as a surprise because for a long time the post-Commodore systems had, at best, shared pages with the classic Amiga in the remaining few magazines such as Amiga Future. This suggested that things had never been peachy enough in the next-gen quarters to justify a dedicated mag. Well, that’s what I thought before I heard of Amiga NG.

Four years ago in Poland they decided to take the plunge and start a magazine to cover the three NG flavours, that is, AmigaOS4, MorphOS and AROS. More importantly (because starting a mag is easy), they were really serious about it. The brainchild of Adam Mierzwa went from a simple PDF-only pilot publication to a full-colour 64-page printed magazine that, at one point, became a regular quarterly and earlier this year made it to issue #10. (This is the part where you say wow!) The efforts of editor-in-chief Mierzwa and his small team have been supported by the Polish publisher Adam Zalepa, whom you may also know as a prolific author of Amiga-themed books and user manuals. Initially unconvinced, Zalepa gradually warmed to the idea of a new magazine, and Amiga NG became part of the impressive range of computer mags published by Zalepa’s company Bitronic. And although I doubt it brings the publisher any profit (considering the low print run, which doesn’t exceed 100 copies), from the buyer’s point of view Amiga NG is certainly not a let-down.

In your hands, the magazine feels unusually heavy with all of its pages printed on thick glossy paper. Very thick in fact – the paper weight surely exceeds that of Amiga Future or Amiga Addict. One cannot help asking if such luxury material is really necessary for a hobby mag, and whether a bit of money could have been saved here to spend it on something else. For example, on page design and typesetting, which is a little crude and basic in Amiga NG. Because quite predictably, the project cannot afford to employ a regular graphic designer, leaving the chief editor responsible for graphic chores on top of his editorial, writing and organizing duties. Someone really ought to come and take the load off the back of that busy Mr. Mierzwa!

As for the magazine content, Amiga NG brings the usual: news, hardware and software reviews, tutorials, reports, interviews, and of course the occasional ad. The 64-page format is rather generous and provides plenty of room for screenshots; it also allows the interviews to go into greater depth. Indeed, I’ve found it is the interview section that is my favourite. The magazine team makes good use of their podcasting experience, so the interviews are well-conducted and bring a lot of interesting information, often spanning several pages. What I especially like is that zeal and optimism do not choke the critical mind. Instead of painting a rosy picture, the mag is often very blunt about the various problems that plague the next-gen Amiga world. I appreciate this realistic mindset, which I think is more beneficial to the platform than self-delusion.

All right, so shall we all now start learning Polish to be able to read Amiga NG? Is that what I’m trying to say here?

No, of course not: the lesson mentioned in the title of this article is purely metaphorical, and has nothing to do with language learning. The educational point is in something else. I’m writing this text because I realize that, for the second time in my life, my Polish neighbours have shown me that a can-do attitude is the perfect recipe for bad times. I can see that whether your computing fun is spoilt by the communist grip or by the frustrating legal mess that is currently ruining the AmigaOS4 ecosystem, you can still have your way if you put in hard work and enthusiasm. From this viewpoint, it appears rather ironic that the international next-generation Amiga scene hasn’t even started contemplating a dedicated periodical to represent itself through – now that we know that users in Poland have had one for several years. Some food for thought perhaps. At any rate, the Polish lesson teaches us that things can be done if the rope is pulled in one direction. Thanks for the reminder, Amiga NG!

Pingback: The Polish lesson – amiga.org.pl